Better Late Than Never! Bill Abbate, PhD '65 in Chemistry, Receives Commencement Robes

July 29, 2024

Abigail Arnold | Graduate School of Arts and Sciences

Bill Abbate earned his PhD in Chemistry from Brandeis University’s Graduate School of Arts and Sciences (GSAS) in the fall of 1965. While he received his diploma, he never attended Commencement in 1966, as he was working and he and his wife had just had their second child. Nearly sixty years later in 2024, Abbate, an involved alum, was having lunch with a member of Brandeis’s Institutional Advancement (IA) office and mentioned that he never attended Commencement and thus never received his PhD hood. With the help of GSAS, IA sent Abbate not only the hood but a full set of regalia – who says Commencement dreams can’t come true? GSAS talked to Abbate about his memories of Brandeis, what his new regalia means to him, and his advice for today’s graduates.

This interview has been edited for clarity.

What did you study at Brandeis, and who did you study with?

I studied ferrocene chemistry with Myron Rosenblum. He was a wonderful teacher, as were James Hendrickson and Saul Cohen. They all had a technique. Hendrickson would know when he was getting away from a student and would look them in the eyes and ask where he’d lost them. The way they presented the material brought you in and along.

It took me about four and a half years to finish my degree; I wrote my thesis starting in September of 1965, while Myron was in Israel – the mail worked beautifully back then! I defended in November of 1965 when he was back in the states. It was a good time to be living in Waltham. Brandeis was much smaller then, and I was treated very, very well, as were all the chemistry students.

What are some favorite memories from your time at Brandeis?

All the professors were interested in all the students in my class. I was not very good at quantum mechanics, and as I was walking down the hall one day, Sidney Golden, who taught it, came out of his office and said he needed to talk to me. He said “You don’t know what you’re doing, do you?” and I admitted that I didn’t. We talked for an hour, and he said to stick it out and that I’d probably get a C, which was fine. We all played baseball on Sundays on the field, and Myron and some of the other faculty periodically joined us. In the summer of 1965, we all had a beach party and many of the professors came too. We babysat for the professors’ kids. There was a very close camaraderie between the students and the professors. It’s very unusual – when I got out in the world and talked to people from other schools, I found that no one had it as good as we had. It was a family!

Myron insisted we only work five days a week and eight hours a day. He said that if we couldn’t do our work in that time, we weren’t doing it right. I don’t know how it worked, but it did! Myron had good postdocs, and they helped and showed us how to do things. In the first few years, we learned how to work in a laboratory from them. I also learned how to study. At least three of us always studied together for each course and went over the material to understand it. One time, we were at dinner at my apartment on a Sunday, and my wife said, “Don’t you have a test tomorrow?” We said that we knew it all because we had spent so much time studying together! That helped make my time in the program much easier.

At our first Christmas party at the Castle, Saul Cohen, the chair of Chemistry, walked up behind me and said, “That’s not a Christmas tree you’re looking at, and that’s not a Santa Claus. That’s just a Chanukah bush and a very old man.”

When my wife and I had our first son after my first year, Myron gave me an increase in my stipend. He increased it from $200 to $250 a month!

What were the campus and the area like when you were there?

The middle of the campus was empty then, except for the three chapels – there was a big green area around it. We mostly had lunch at the Castle. We also went to seminars, a lot of which were at MIT and Harvard. We went to Harvard to see Robert Woodward, the Nobel Prize winner, who had been Myron’s mentor – he always invited us to his seminars. We got a great education!

We were in Boston at a beautiful time. The Gardner museum and Museum of Fine Arts were free, and my wife and I would go down with the baby in a stroller on the weekends.

What have you been doing since graduating?

I went into industry. At the Upjohn Company, I bought one of the first Hewlett-Packard laboratory computers so data could be entered there instead of written down by hand. Before that, I was adding up handwritten pages on a calculator. While working there, I ended up going to Tokyo for almost eight years, which was a great experience. I have spent my retirement studying history and religion and all the things I didn’t take in college. I went to college at the time of Sputnik, so we were all told to study science; for my degree, at least twenty of thirty-two courses had to be science. I think you lose a lot by not taking the liberal arts and a wider range of courses. Not taking only science courses won’t make a difference in your ability to get a graduate degree.

What does it mean to you to receive your Commencement hood and regalia now?

I brought it up as one of the things I’d missed when I was having lunch with Bruce Siegal from IA. I then got an unexpected package from UPS – it broke me up. That’s Brandeis, that’s the feeling of Brandeis! I told him I would love to go to Commencement and then he sent it to me because I felt that I missed it.

What advice would you give to this year’s PhD graduates?

It’s not about you: it’s about the people. If you’re a manager of a group, you’re doing it for them and not for yourself. When I worked with Mitsubishi in Japan, the group explored many different options, but once they picked one, they were all behind it. Work for others and not yourself.

Fun Facts: Then and Now

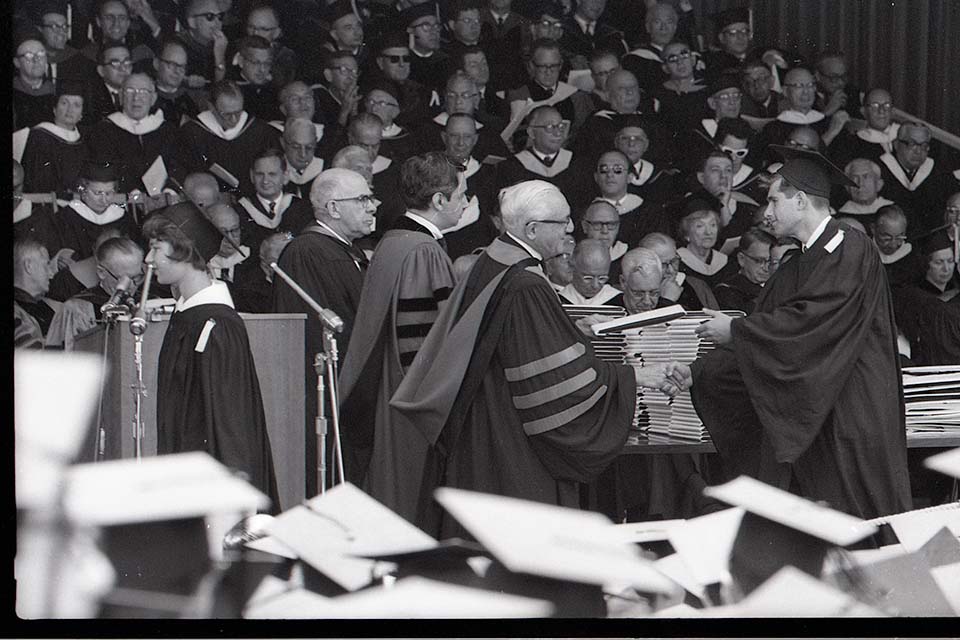

In 1966, when Abbate would have attended his original Commencement, the speaker was Arthur Goldberg, the United States ambassador to the United Nations. Other honorary degrees went to Erwin D. Canham (editor in chief of the Christian Science Monitor), Andrew W. Cordier (dean of Columbia’s graduate school of International Affairs), David Dubinsky (labor activist), Avraham Harman (Israeli ambassador to the United States), Henry T. Heald (former president of NYU and the Ford Foundation), Barnaby C. Keeney (chair elect of the National Endowment for the Humanities), Francis Keppel (government education official), Isador Lubin (Brandeis trustee), and Benjamin H. Swig (Brandeis trustee).

In 2024, the Graduate Commencement Speaker was Ruth J. Simmons, president emerita of Brown University. Other honorary degrees went to Ken Burns (documentary filmmaker), Roy DeBerry (GSAS MA ’78 and PhD ’79, a civil rights activist), Rabbi David Ellenson (late president of Hebrew Union College), and Ruth Halperin-Kaddari (lawyer and academic director of the Ruth and Emanuel Rackman Center for the Advancement of Women’s Status).

10 GSAS students received degrees at the 1966 Commencement. 217 GSAS students received degrees at the 2024 Commencement!