English PhD Student Jenny Factor Explores Phillis Wheatley Peters's Poetic Games

February 18, 2025

Abigail Arnold | Graduate School of Arts and Sciences

Jenny Factor is a seventh-year PhD student in English at Brandeis University. Her research interests include Pan-Atlantic eighteenth century media history, Black bibliography, poetry, and gaming. For Black History Month, she spoke to GSAS about her research into Black New England poet Phillis Wheatley Peters and her use of games in her poetry.

This interview is in Jenny's own words, with slight edits for clarity.

My Research

I study eighteenth-century Black New England poet Phillis Wheatley Peters, focusing on her evolution from a poetic game player to a virtuosic game maker. By tracking little word games inside her poems, my dissertation brings a close study of material culture—such as furniture, board games and broadsides—together with literary evidence to tell a story in four acts, tracing how Wheatley Peters arrived from Senegambia with an extraordinary mind for poetic play, sharpening her skill through iambic pentameter church aphorisms to the point when she entices other artists to play newly invented games to the rules she sets. When we take on the question of where the art and craft of an enslaved girl of West African origin fits into the leisure judgements and possibilities of a diverse local crafts-and-trade community and a white, cultured, enslaving household, we find new access points to Wheatley Peters’s aesthetic vision and to her home- and town’s pan-Atlantic view of the world.

What Drew Me To This Topic

I discovered the vibrancy and strangeness of a particular, under-read subset of Phillis Wheatley Peters’s poems during a first-semester Brandeis graduate course on the Fictions of Revolution. Something about her manuscript/handwritten poems and the circulated aspects of her verse caught my attention. Moving outside the reach of the printing press, these handwritten versions of Wheatley Peters’s poems did what I think poetry does best: they helped to define small communities; they reveled in their own virtuosity; they created a small world and then inhabited it; they played games with specific other people.

I had been fascinated with the community aspects of poetry for a long time. Before I returned to graduate school, I taught poetry at a low-residency MFA program devoted to literature and social justice. Through that work, I learned the myriad inspirational ways our adult students were using literature to build bridges and make change in their immediate lives. I began to wonder if this poetry of affective immediacy was one liberatory aspect of Wheatley Peters’s verse—not the message(s) per se, but the craft and play and means.

Why I Think It’s Important

My hope is that this work will give us an added access point to some of the aesthetic fascinations of a truly important African American poet, while opening up a new conversation about literature-and-leisure in the eighteenth century New England world. And—if all goes well—there’s a possible larger goal of beginning to point to a different way of reading poetry beyond any interest in aesthetic posterity and out toward an instrumental experience of play and delight. To build a methodology for this kind of reading could really matter: it may open up a way of looking at poetry that values community. It may offer us an alternative for building a diverse canon that retrieves those poems at their site of primary power—the family, the region, the town—recognizing and valuing the judgments of small circulation groups rather than relying on print alone.

My Experience Getting Grants

My 2023-2024 project work was really transformative. I ended up fully funding my sixth year from grants, staying in fellowship housing and learning and posing questions in small, inquisitive, caring scholarly fellowship communities. Dorothy Kim, my dissertation director, strongly advocated for using the dissertation years to seek out archives and wider scholarly conversations. She helped me think in particular about how the scaffolding of ideas with which I was working might benefit from my going to see some early American board and card games. Together, we made a list of research fellowships and funding sources, and I applied to six archives and two outside funding sources.

I spent two weeks at Emory looking at what they call the Phillis Wheatley copybooks, four weeks at the John Carter Brown Library steeped in early American periodicals and their puzzle and poetry sections, and six weeks or so at Yale’s Lewis Walpole collection in Farmington, Connecticut learning about visual print culture, leisure, and humor and moonlighting with the riddle books at the Yale Center for British Arts and the card games at the Beinecke Library. I began to work on a digital edition of Wheatley Peters’s circulated poetry variants with the KU/Champagne-Urbana Black Books Interactive Project/Afro Publishing without Walls, a great online cohort of scholars. And most transformative of all, I spent six months spread over a year at the Winterthur Museum, Garden, and Library, where a team of experts in early Americana seemed ready to engage with my questions at any time, dawn to day’s end. I walked in the forests, climbed past the dairy barns, checked out books from the library, and actually got to see the back end of their archives; after every one went home, I would sit in the fellows’ office in a deep quiet. The Mandel Center at Brandeis and Campus COMPACT helped make all of this possible through a dissertation innovation grant. At each place I went, some archivist and conservator set aside their own stunning research to help me connect dots on my project I at first didn’t even know existed.

My advice to other students applying for grants comes in two parts: first, as Dorothy showed me, do write an interested archivist or the fellowship contact person in advance, allowing them to help you think creatively about how their collections might speak to your questions. Then if all goes well, you’ll be writing a proposal that lays out a functional well-scheduled research plan, and you can feel like the application is just the start of a more ongoing conversation. The second piece of advice is to apply. I’ve been able to use nearly every paragraph I’ve written for a fellowship application in the dissertation itself too. Yes the applications take time, yet learning to explain one’s research to an interested outside audience is not time away from the dissertation, it’s the whole point.

One Amazing Find

Phillis Wheatley Peters’s writing desk was not a desk at all! It was a petite folded-top mahogany card table that one would find in a New England home’s front room parlor. One side of the table was even laid out with a specialized game top for playing cards and gambling with ivory game counters. I had the chance to examine this table, housed at the Massachusetts Historical Society, with Winterthur curator emeritus of American furniture and Boston furniture archive co-founder, Brock Jobe, who interpreted the table’s construction and use in a brand new way, and to discuss its significance to Wheatley Peters’s “maker space” with Brock and current Winterthur curator of American furniture, Josh Lane, who together spent countless hours helping me learn how to “read” the materiality of a table as a story and to contextualize this one within its wider connection to New England literature and visual art. Jackie Killian, Kathy Gillis, Anne Bentley, and Peter Drummey filled out the team of people who helped me gain access to the table and think through what our findings meant.

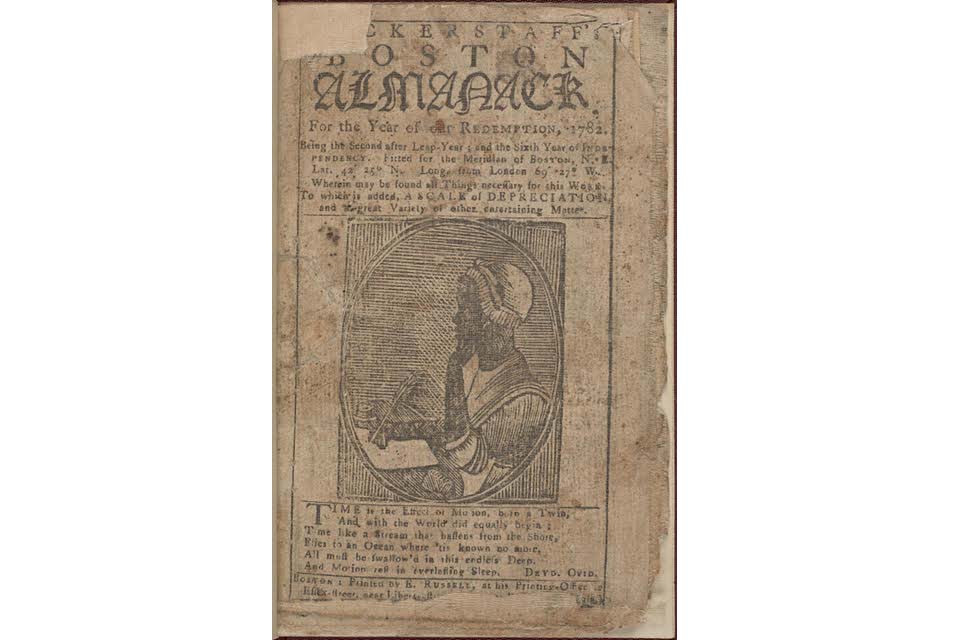

The public domain image of Wheatley Peters at the top of this article was accessed on a Creative Commons licence from the New York Public Library.