These Books Speak Volumes

The Nazis systematically looted Jewish libraries during the Holocaust. Today, the books that have been recovered serve as evidence of a traumatic time, memorials to people lost, and artifacts of a rich cultural heritage.

By Emily Gold Boutilier

Photography by Gaelen Morse

WATCH: The Jewish Restoration Project - How Brandeis is writing a new chapter for Nazi-looted heirless works

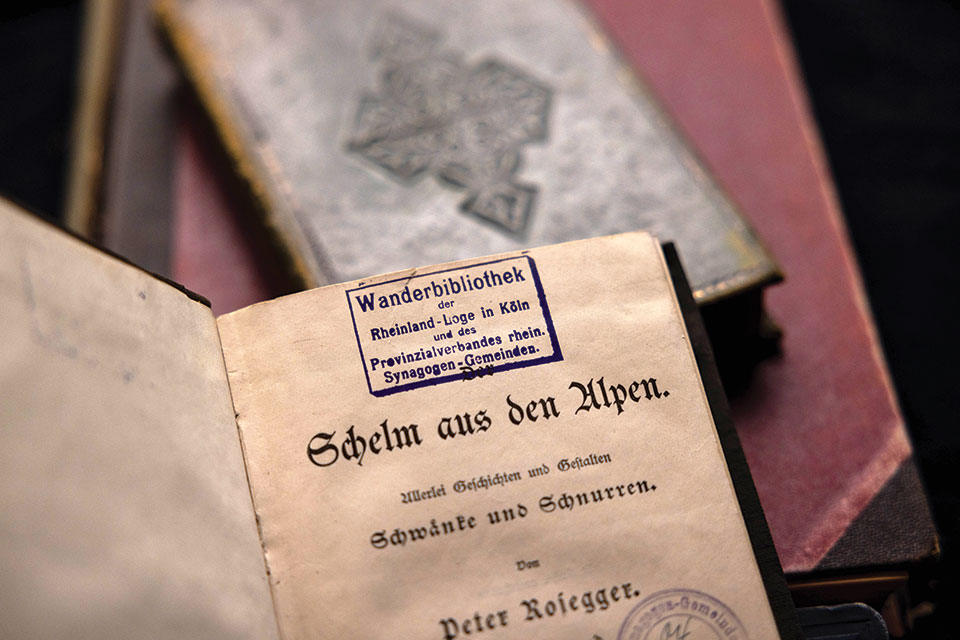

Meiner lieben guten Marta dem 22t November 91. Hugo.

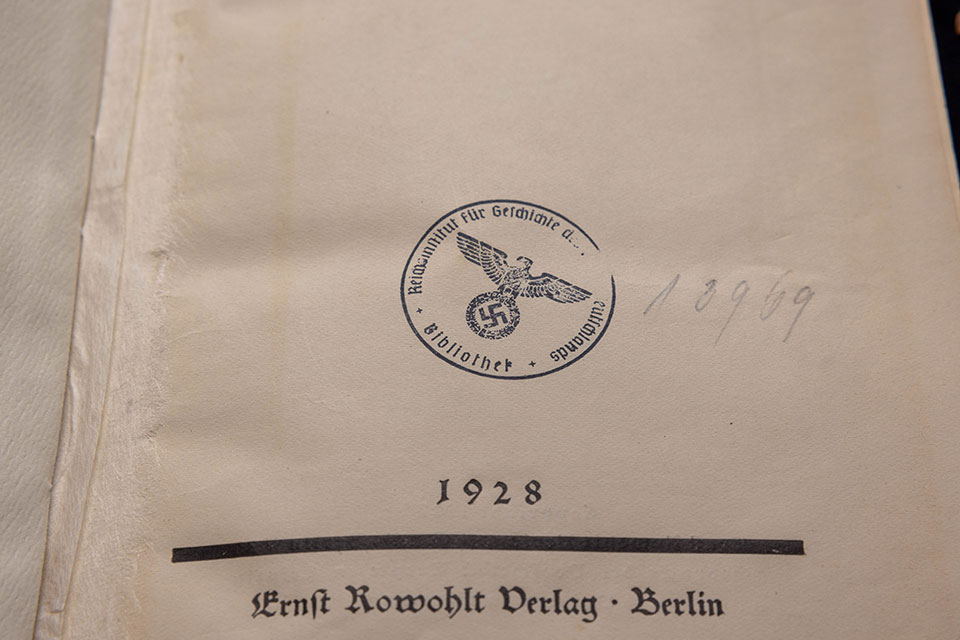

Brandeis librarian Lou Hartman found this handwritten inscription, translated from German as “To my dear good Marta on the 22nd of November [18]91 — Hugo,” inside a dusty hardcover of “The Coming Days,” a play by 19th-century German Jewish author Hugo Lubliner.

Below the inscription is a stamp depicting an eagle; a few words in German; and, in ink so faded most people would miss it, a swastika. When Hartman (who uses they/them pronouns) saw the stamp, they took a sharp breath. It was exactly what they sought to find: evidence the Nazis had looted the book during the Holocaust.

Who was Marta? Was the Hugo who inscribed the book the same Hugo who wrote the play? Who else read the book between 1891 and 1952, when it traveled across an ocean to help seed the new library of a new university founded in the aftermath of World War II?

We will likely never know. But we do know that “The Coming Days” is among the books stolen by Nazis from Europe’s Jewish homes, libraries, community centers, and synagogues. The Nazis looted books not always to burn them but, in many cases, to study them, as part of a convoluted plan to scientifically justify the Holocaust.

Allied soldiers recovered millions of these books during and after World War II. In 1952, records show, Brandeis received exactly 11,288 of them from Jewish Cultural Reconstruction Inc., an organization created to redistribute heirless Jewish cultural property. The cache of books Brandeis got was among the largest number given to any institution in the world.

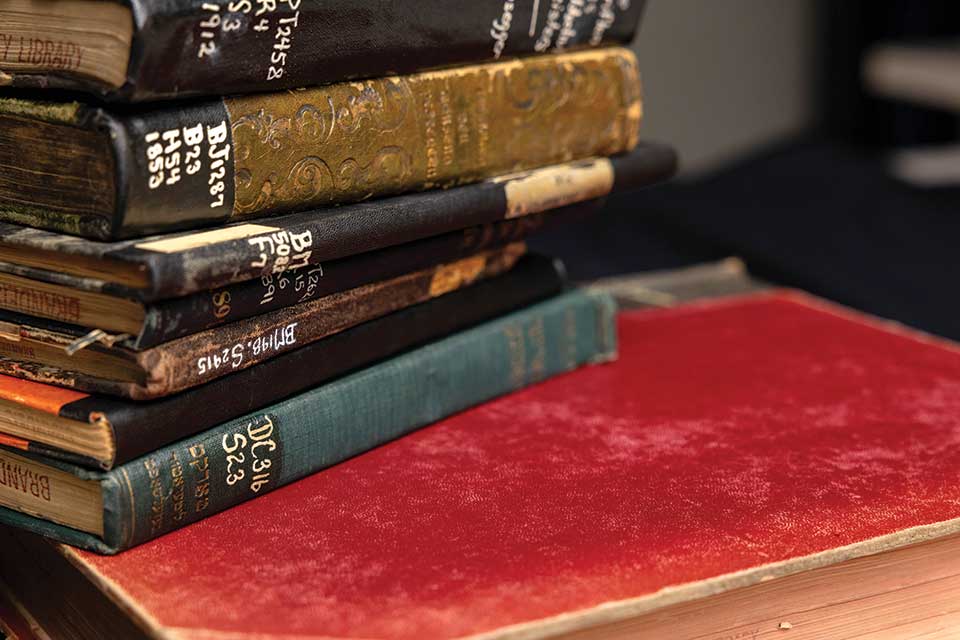

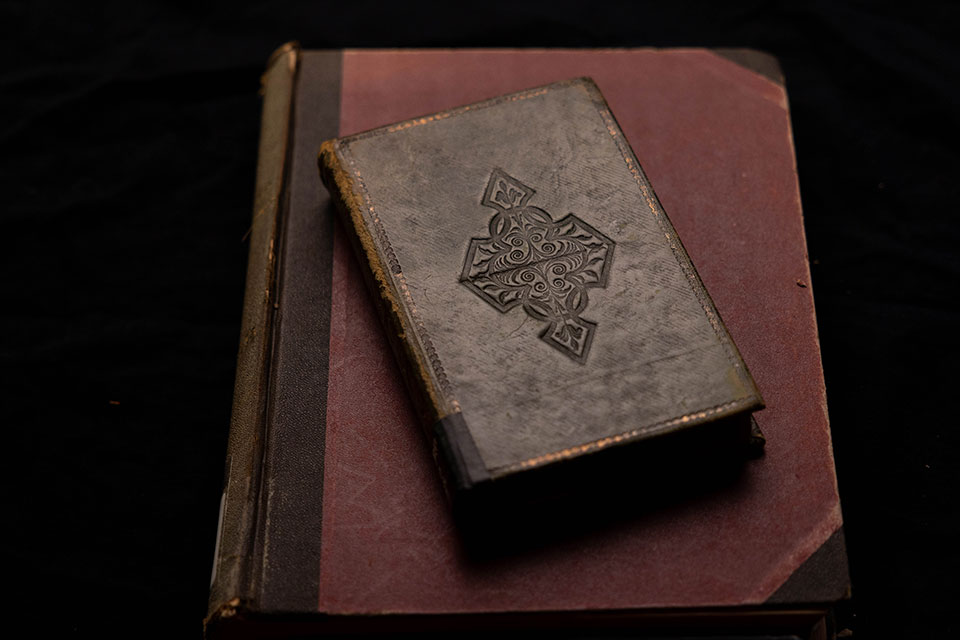

Unlike Nazi-looted art, these books are neither rare nor valuable. From popular novels, to chemistry texts, to prayer books, they are the everyday books of everyday people. For more than seven decades, they have lived among all the other books in the Brandeis stacks, organized by subject matter and author, checked out by students and faculty with interests in Aristotle, or Goethe, or Freud, or the Talmud.

Now Hartman and others at Brandeis are combing the shelves to identify and preserve as many of them as possible. Similar work is underway at other universities and libraries, which see these books as material evidence of the Holocaust, memorials to those who were murdered, and a treasure trove of European Jewish cultural and intellectual history.

No other relic of the Holocaust can perform all these roles at once. Consider the shoes on permanent display at the U.S. Holocaust Memorial Museum, in Washington, D.C. These shoes, confiscated from men, women, and children upon their arrival at Poland’s Majdanek concentration camp, are striking evidence of a collective trauma but not a collective culture. You need to read the humanity of those who wore them between the lines.

“Yet you can actually read one of these books,” Hartman says. Your hands can touch the exact pages the hands of every previous reader touched. Your brain can absorb the exact words printed in the exact ink.

It’s like walking in those readers’ shoes.

“And when there’s an inscription, I have to sit with that for a minute,” Hartman says. “I know that name may be the only thing left to show a person existed.” The inscriptions often include the date of a happy occasion: a birthday, a wedding, a vacation. When Hartman sees a date, they wish they could shout a warning: “I want to reach back through history and say, ‘You’re in Berlin in 1934. Get out of there.’”

Plunder, rescue, and return

The story of the heirless books’ migration to Brandeis begins in the 1930s, when the Nazis devised a plan to systematically plunder volumes from the private, community, and scholarly libraries of Jews in Western and Eastern Europe. Some books they burned. Others they sent to their Institute for Research on the Jewish Question, in Frankfurt, Germany, where antisemitic policies were developed in support of the Holocaust.

Books were studied at the institute “with a very, very evil intention,” says former Brandeis instructor David Fishman, now a history professor at the Jewish Theological Seminary. Fishman is the author of “The Book Smugglers: Partisans, Poets, and the Race To Save Jewish Treasures From the Nazis” (published in 2017 and later acquired by Brandeis University Press), which details the effort by ghetto residents in Vilna, Lithuania, to rescue Jewish-owned books and cultural treasures.

The Nazis wanted to prove their antisemitic theories using science. Science requires primary sources — books, for example.

“If you enter an investigation with a preconceived notion, lo and behold, everything you find only proves you right,” Fishman says. “They never doubted that every book would show, if read ‘correctly,’ just how evil and depraved the Jews are.”

The Nazis looted books not always to burn them but, in many cases, to study them, as part of a convoluted plan to scientifically justify the Holocaust.

As the war drew to a close, the U.S. Army sent soldiers to recover looted Jewish-owned art, books, and other cultural heritage materials. These so-called Monuments Men rescued mountains of books, warehousing them first at the Rothschild Library in Frankfurt, then in a five-story building in nearby Offenbach. The previous occupant of what became the Offenbach Archival Depot was the chemical company IG Farben, whose subsidiary supplied Zyklon B, the poison gas used in the death camps.

From Offenbach, 3 million books were returned to their rightful owners — primarily large institutions such as the YIVO Institute for Jewish Research, which had moved from Vilna to New York City during the war. But numerous other books had no known heirs. International law specifies that heirless items belong to their country of origin. Yet Jewish institutions objected. European Jews no longer belonged in those countries of origin. Why should their books go to Poland, or Germany, or the Soviet Union?

“The people who owned these books before the war were murdered,” Fishman says. “The institutions that owned them were destroyed.”

Ultimately, the U.S. military made an unprecedented decision. The heirless books belonged not to a country, but to a people — the Jewish people.

Heirless works find a home

The question of where to send the books echoed the question of where to send the Jews who survived the Holocaust. The answer was largely the same: to the United States and Israel.

In 1947, Jewish Cultural Reconstruction Inc. formed, with German American philosopher Hannah Arendt as an executive. In 1949, U.S. military authorities, facing pressure from Jewish leaders, agreed that JCR would disseminate the heirless books at Offenbach.

In between, Brandeis was founded, in 1948. One of the most pressing tasks of any new research university is to stock its library — not with rare or special books, but with books in general, in all subject areas, in all languages. This is probably one reason JCR named Brandeis a priority library.

Only three U.S. institutions received more JCR books than Brandeis did. The collection that came to Brandeis included works of Jewish history and theology, and books on German literature and theater, by both Jewish and non-Jewish authors. There are many books about psychoanalysis, including a Yiddish translation of Freud. There are math textbooks, sheet music, periodicals.

These volumes found a new home in the library stacks at Brandeis. And that’s where they remained for seven decades.

Your hands can touch the exact pages the hands of every previous reader touched. Your brain can absorb the exact words printed in the exact ink.

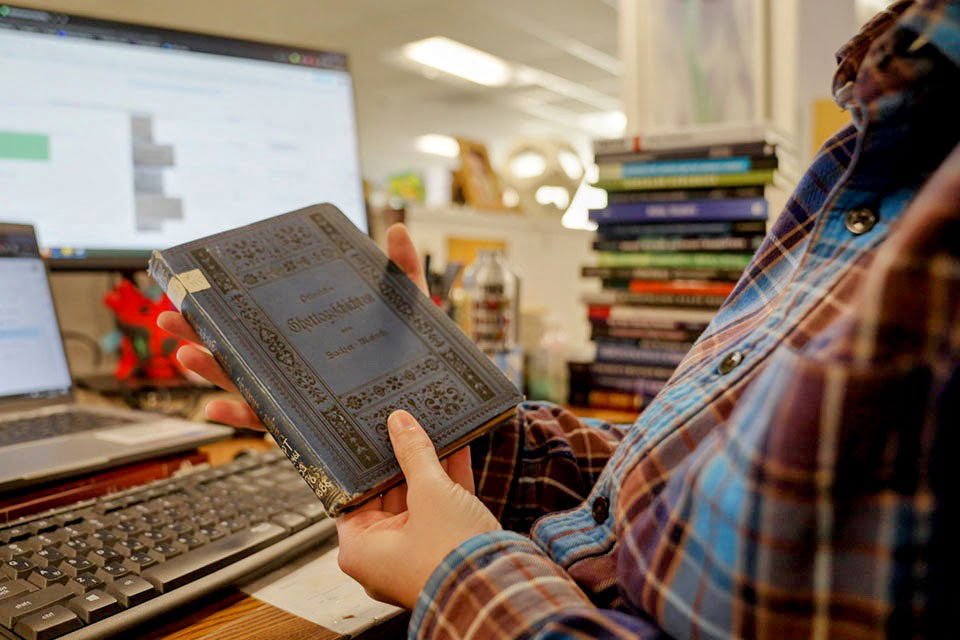

Then, in 2022, three Brandeis staff members — Hartman (who is a metadata coordinator), Rachel Greenblatt (Judaica librarian), and Ari Kleinman (metadata librarian, Hebrew specialty) — set out to locate, catalog, and learn about the JCR books among the stacks. Their primary goals were to ensure the books and their provenance information are preserved, and the books are cataloged in a way that readers can easily find them.

The librarians identified 60,000 books published before 1945. Now Hartman and a team of student workers are combing the shelves, plucking out these books one by one, and searching each for a telltale marker: a Nazi stamp, an Offenbach stamp, or a JCR bookplate. Of the 50,000 opened so far, there are 67 with a JCR plate, 168 with a Nazi stamp, and 393 with an Offenbach stamp.

Hundreds more books have stamps from a European Jewish institution. These may or may not have been looted, since Brandeis received donations of European Jewish books from sources besides JCR, including the Brandeis University National Women’s Committee (now known as the Brandeis National Committee) and individual book owners who immigrated to the United States before the Nazis gained power.

At the same time, the absence of a stamp or a bookplate in no way proves a book was not looted. Such markers were inconsistently applied, and some surely fell out or faded over time. “If the book was damaged over the years, we re-bound it,” says Hartman. “And in those cases, if the stamp was on the inside cover, which it often is, we wouldn’t have retained it.”

As the Brandeis librarians learn about the books, they are helping others do the same. Through the Association of Jewish Libraries, Greenblatt and Kleinman have created an information-sharing group of librarians engaged in JCR cataloging work. With Brandeis as a partner, Maryland’s Towson University received a $250,000 federal grant from the Institute of Museum and Library Services to support the librarians’ efforts — and to use the books in Holocaust education.

A people of books

When someone we care about dies, we often want to keep something they owned: a sweater, a coffee mug, a watch. In treasuring what they treasured, we remember them.

“The vast majority of European Jews were murdered,” says Fishman. “Most Jewish architecture — institutional buildings, synagogue buildings — was destroyed. What do we have that reminds us of European Jewry? I think the most tangible thing we have is the books.” At Brandeis, these include five copies of the 1928 Encyclopaedia Judaica. Markings show they once belonged to the Central Association of German Citizens of Jewish Faith, an organization founded by German Jewish intellectuals to counter the rise of antisemitism in their country.

According to Yad Vashem, the Holocaust remembrance center in Jerusalem, the Central Association worked hard “to convince the Nazi government to recognize the Jews as a separate but equal group within Germany.” After Kristallnacht, the Central Association ceased to exist independently. At some point, the five encyclopedias acquired Nazi stamps.

“Most Jewish architecture was destroyed. What do we have that reminds us of European Jewry? The most tangible thing we have is the books.”

Professor David Fishman

We don’t need lists of names to know the fate of the Jews in the Central Association; we can fill in that blank. These facts remain: The German Jews who read the Encyclopaedia Judaica existed. The Nazis sought the book to use it as a weapon, stealing five copies from Jews who could hardly believe they were no longer German. The U.S. acknowledged these copies belong to the Jewish people. The Jewish people decided they belong at Brandeis, where five copies of the Encyclopaedia Judaica helped create a library that has benefited scholars and students for 76 years and counting.

Perhaps no looted book in the Brandeis collection makes this point more powerfully than “Maskerade,” a play by German Jewish playwright and translator Ludwig Fulda. It contains a handwritten inscription from Fulda to two of his friends, dated Dec. 13, 1904, signed in Frankfurt.

Fulda was well known and accomplished. His most famous play, which retold the folktale “The Emperor’s New Clothes,” was “Der Talisman” (a few copies of which are at Brandeis, one carrying a Berlin bookstore sticker).

In 1906, Fulda visited the U.S. The New York Times reported on that trip, including his attendance at a staging of “Maskerade” at the Irving Place Theatre. Seven years later, Fulda visited again, and the Times ran a lengthy profile.

The Times ran yet another article about Fulda in 1939. It was his obituary. Here are a few lines: “Friends said one of the anti-Jewish measures which affected him most keenly was the Nazi law requiring him to register his name as Ludwig Israel Fulda, inserting the ‘Israel.’ Since the beginning of the Hitler regime Dr. Fulda, who ‘retired’ from the Prussian Academy of Arts along with Thomas Mann, Franz Werfel, Alfred Döblin, and others in 1933, had been living quietly in Berlin.” According to the Times, “the regular German press took no note of his death.”

That’s not the end. A 1943 article in the Times reintroduced readers to Fulda, whom it now called “a forgotten playwright.” The reporter says Fulda found it impossible “to assimilate the concept of no longer being considered a German. He was stunned and […] never recovered until he died.”

What these articles elide are reports that Fulda was denied a visa to the U.S. and that he killed himself. He did not survive the Nazis. He was “forgotten” soon after his death.

Now you know his name. You know he visited New York at least twice. You know he retold the story of “The Emperor’s New Clothes.” You know he inscribed a book to two friends.

With these fragments of knowledge, you become a keeper of his memory.

Emily Gold Boutilier is a freelance writer living in Amherst, Massachusetts.