In Constant Search for New Forms of Resistance

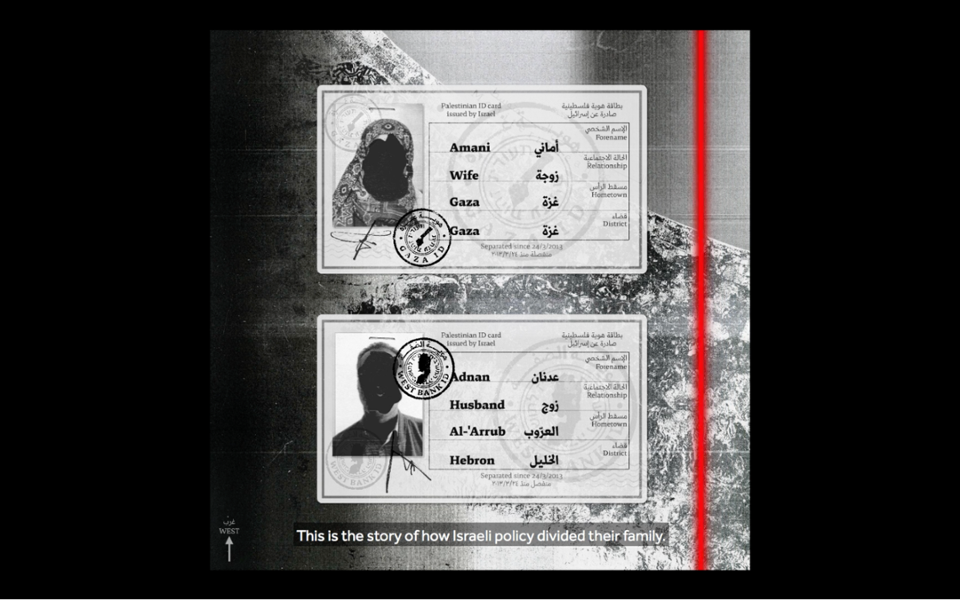

Still from So Close Yet So Far video series. Source: https://vimeo.com/460585099

By Yosra El-Gazzar , CEC Artslink Fellow at the Program in Peacebuilding and the Arts

The search started in the winter of 2016, and it's still ongoing. I was a young fresh graduate from an art school in Cairo, and I was filled with excitement for the fact that my graduation project was selected to be showcased in a high-end art exhibition. It was my first participation in an art show, and my first encounter with the reality of the contemporary artworld. I guess I was lucky to find early on how art can be a medium of communication about the subjects that matter, at least to me and my community. My project was about the borders of the Middle East, and the restrictions of movement in the region. I was fascinated with the information I found during my research. The result of months of research and tons of information was met with a limited gallery space, where people spend five minutes absorbing what I spent a long time carefully weaving together.

I guess it's a stopping point that every socially engaged artist gets to encounter, and question what we are doing and whether our voices are really getting through the right channels, to the right people. I never doubted the role of the arts; art has always been a medium of the people. Communities celebrate their rituals together, through art. They connect to nature, through art. They speak about their struggles, through art. However, the questions of my father sometimes echo in my head. My father, the doctor, who saves lives, always challenges me for what I do, and questions its importance. The ego of the artist in me would get into an automatic defensive mood. Of course, art matters. Of course, it contributes to societal change.

Putting the ego aside, I think it's good that we, as contemporary artists especially, stop, reflect and self-criticize. I come from a part of the world that is filled with unheard voices, with stories of deep injustices that are begging to be spoken about with a reflective and free voice. But I also come from a part of the world where the practice and sharing of certain kinds of art remain a luxury. The confinement of art within the borders of art galleries, lectures and symposiums, that are mostly attended by the same crowd, remains distant from the realities of everyday street life.

This is a rather dystopian picture, and is partly unfair to the many efforts that have been taken in the past years to bring contemporary means of art closer to the general public. I am grateful to have found a space within those efforts, but I remain in a constant state of questioning. Is the kind of art I create even meant to be accessible to the majority of the public? And how could I make my art accessible, without making it lose its poetry?

In 2016, I joined the team of Visualizing Palestine. Again, I was lucky. Visualizing Palestine is an organization that uses research and data-based stories to build factual visual narratives about the Palestinian/Israeli issue. It's an impact-based organization that works on bridging this gap between art and the people, for the sake of an on the ground real narrative change. Their impact numbers testify to this. Their work has been used in more than 76 countries around the world, in areas where you would not imagine that the Palestinian issue would be that visible. It was also successful in building solidarity movements across the world, highlighting the similarities of injustices between different groups that are facing constant discrimination and marginalization.

(The year) 2018 was a turning point for me as a socially and politically engaged artist. I worked with the VP team on creating a video series called So Close Yet So Far. It's a series of five stories that tell actual narratives of Palestinian families separated because of a cruel apartheid system. Families that live as close as 2km apart, yet cannot see each other for years. Many people speak about the situation in Palestine, yet many stories remain unspoken about, for a reason that is beyond my logical understanding. And I was faced with this challenge: how can we tell such stories in a way that remains true to their original narrators, accessible and widely shared with a global audience, and at the same time have the artistic power that transmits the deep emotions behind each story?

We created a short, less than two-minute video, for each of the five stories, which made them widely accessible, and shared them through social media channels. The team came up with the idea of comparing local distances of separation inside Palestine to regularly navigated commutes in major cities worldwide. For example, the distance between Gaza and Al-Arrub in Palestine is almost equal to the distance between Amsterdam and The Hague, a distance that takes less than 45 minutes with public transportation in the Netherlands. Yet, a Palestinian wife, Amani, in Gaza city, couldn’t see her husband in Al-Arrub, for more than four years. The children couldn't see their father, either.

I'm not a big fan of social media, I have to say. Even though I belong to a generation that witnessed a social media organized revolution in Egypt and several other countries in the region. Yet again, after the release of "So Close Yet So Far," I felt the same feeling after my graduation exhibition. Are our voices really coming through? Are we compromising on the experiential characteristics of art for faster consumed forms? Are we following the trends rather than reflecting on them?

I have recently shifted my efforts more towards cinema, while I still shuffle between visual arts, graphic design, and writing. I don't think it's where I'll find the solution, but I also think it's more important to ask the questions, and to be in a constant search for new forms of resistance.