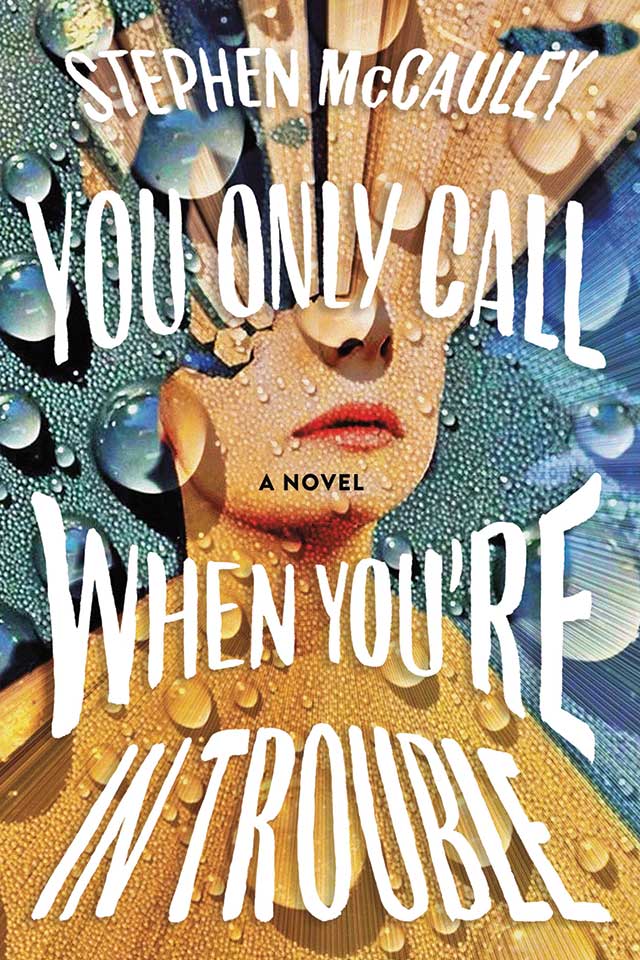

Stephen McCauley Answers the Call

His latest novel gives his fans what they crave: a smart comedy of manners, filled with genuine psychological insight.

Photo Credit: Sharona Jacobs

By David Levin

For more than 30 years, reviewers have lauded Stephen McCauley’s ability to craft witty, insightful novels and intricate literary worlds.

It’s no surprise, then, that — from its first page — his 10th novel, “You Only Call When You’re in Trouble” (Macmillan, 2024), plunges readers into a funny, poignant romp through its characters’ lives, weaving their stories together with the dexterity of a Jane Austen classic.

Tom, an aging architect at a career turning point, is finally designing his masterpiece, a small yet elegant guesthouse for a tony client in a Boston suburb. If anything goes wrong, his firm will fire him.

Simultaneously, he’s in the midst of two family crises. His sister, Dorothy — a flighty single mom who often leans on him for financial support — has been drawn into a questionable real estate deal. Her business partner, the washed-up self-help author Fiona Snow, has bullied her into buying a massive “retreat center” in Woodstock, New York, where Fiona plans to revive her fading glory on Dorothy’s dime by hosting inspirational workshops.

To make matters worse, Dorothy’s daughter, Cecily — whom Tom cherishes — is facing a trumped-up Title IX investigation at the small liberal arts college where she teaches. Her career and her relationship with her boyfriend are headed for the rocks.

As McCauley’s characters navigate these difficult yet quietly hilarious scenarios, their lives bend under the strain. Can Dorothy finally reel herself in and take responsibility for her choices? Will Cecily find happiness as an academic? Can Tom save his family and his career?

When the three family members converge at the retreat center for its grand opening, they’re almost at the point of resolving some old grudges and co-dependencies. Suddenly, Fiona reveals a long-held secret: the identity of Cecily’s father.

Throughout the novel, McCauley, professor of the practice of English and co-director of Brandeis’ creative writing program, artfully discloses small but telling details about his characters, which often challenge readers’ prior assumptions. After establishing Fiona as an aggressive, overbearing personality, for instance, McCauley includes a chapter written entirely from her perspective. Over the course of a few pages, he rips off the facade of unearned confidence Fiona has been hiding behind, showing her crippling self-doubt and chronic disorganization.

“The chapter gives her a little bit of redemption and shows her vulnerability,” McCauley says. “I always try to see conflicts from the other person’s perspective. That’s a big job of the fiction writer — to see behind your character’s defenses, to know what’s motivating them or what they’re trying to hide from the world.”

McCauley’s books are rich with astute observations of social interactions, a trait he says comes from his feeling like an outsider for much of his life. Growing up in Woburn, Massachusetts, he was the lone recreational reader and writer in a family who wondered aloud why he didn’t just put down his books and watch television with the rest of them. Coming out as gay in his teenage years only exacerbated the familial distance, he says.

After graduating from the University of Vermont in 1978, he held a series of odd jobs — kindergarten teacher, travel agent, yoga instructor, housecleaner — each of which reappears in his novels to full comedic advantage.

In the 1980s, he moved to Brooklyn and earned an MFA at Columbia. In 1987, his debut novel, “The Object of My Affection,” was published to critical acclaim. Its main character, George Mullen, a gay kindergarten teacher, is kicked out of his home by his lover, only to be rescued by sympathetic Nina Borowski, whose apartment and life he readily moves into. Just as George and Nina are settling into sex-free domestic bliss, she discovers she is pregnant by a suffocating boyfriend who wants to marry her. In 1998, the book was adapted into a hugely successful film, starring Jennifer Aniston and Paul Rudd.

Most of McCauley’s novels revolve around a strikingly similar main character — namely, a mildly insecure, self-effacing gay man. “That character has evolved in various ways but has aged in similar increments to the writer,” he explains.

People close to McCauley often find themselves embedded in his novels as well. The seeds for his latest book, for example, were sown during a conversation with an old friend, who told him she felt responsible for taking care of her sister in retirement.

“Her sister is someone who has a job, is very intelligent, never takes advice from anyone, and never really seems to learn from her own experience,” McCauley says. “She just resists acknowledging mistakes she’s made. I began thinking about what it would be like to feel responsible for that person, and the story emerged from those dynamics.”

As he works on his next book, McCauley is beginning once more with a character who roughly resembles himself. But, at 68 years old, he’s starting to rethink his narrator’s voice. Instead of leaning toward the wry and comedic, he’s planning to break with tradition and attempt a more somber tone.

“I’m at an age where the chickens are coming home to roost for me and most of the people I’m close to,” he says. “The consequences of decisions and mistakes made earlier in life start to emerge more glaringly, whether they’re financial complications, career disappointments, or just having bad ankles because you wore shoes that were three sizes too small for years.

“It’s always more interesting to write about problems than triumphs.”