Perspective

The Public Square and the College Quad

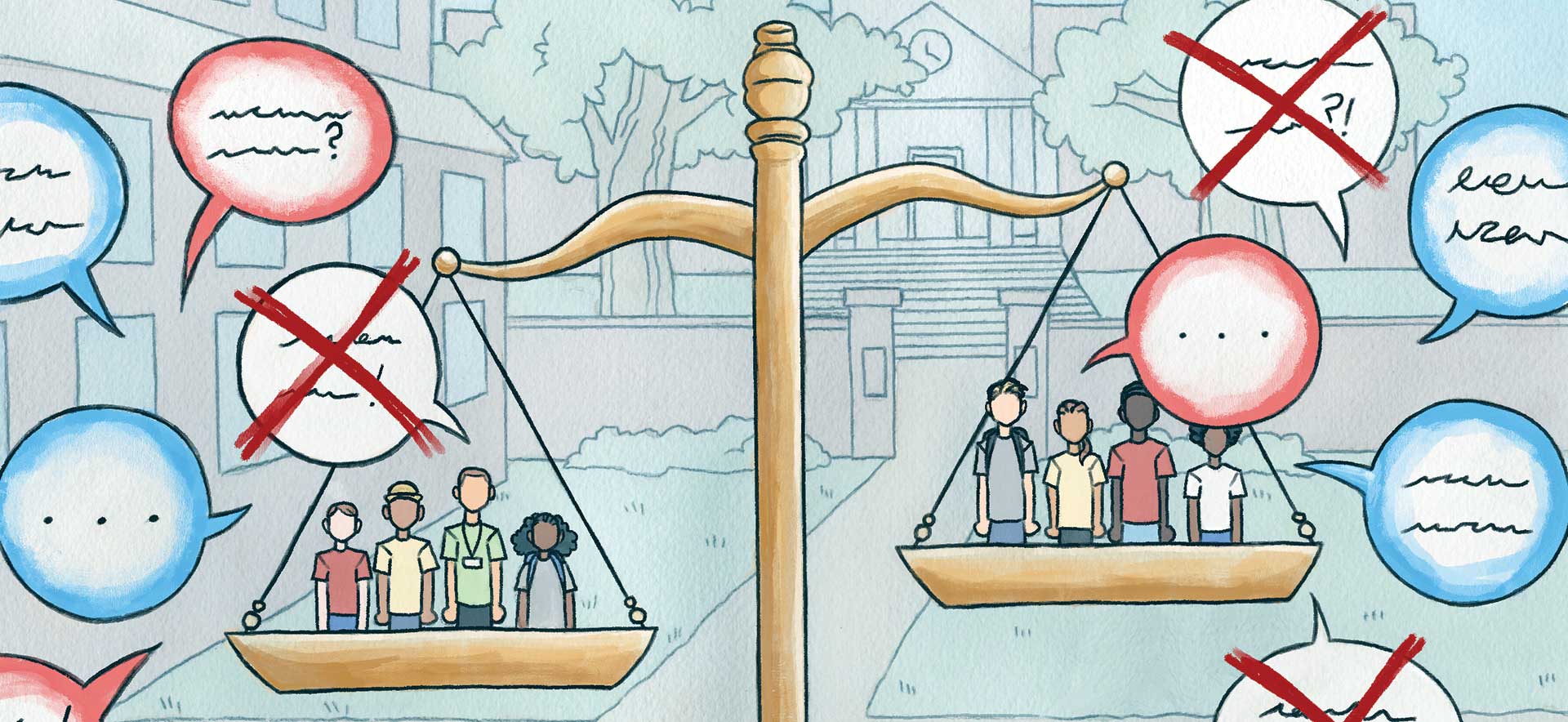

Can universities guard the constitutional right to freedom of expression while protecting students from hate speech?

By Daniel Breen and Rosalind Kabrhel

“If there is any fixed star in our constitutional constellation, it is that no official, high or petty, can prescribe what shall be orthodox in politics, nationalism, religion, or other matters of opinion. …”

These words — written in 1943 by associate justice of the Supreme Court Robert Jackson — remain a fair summary of the comprehensive breadth of the modern First Amendment. A government actor can almost never prevent or punish the expression of an idea of any sort. If the expression of an idea isn’t libel, if it isn’t obscenity, if it isn’t calculated to spark imminent violence, it is probably beyond the reach of criminal law.

Only a law “narrowly tailored” to serve a “compelling state interest” can survive court challenges if it purports to regulate an idea. This standard, known as “strict scrutiny,” is all but impossible for a state to meet.

There is bipartisan support for broad freedom of speech. Court decisions on First Amendment cases, unlike other constitutional issues, are not split along party lines. Both conservative and liberal Americans chafe at the idea of government regulation or suppression of speech.

But things get more complicated when speech is categorized as hate speech, which the United Nations defines as discriminatory or pejorative language used in reference to another person based on that person’s membership in a certain racial, religious, ethnic, gender, or national group.

In the United States, hate speech is constitutionally protected. Understandably, groups on the receiving end of hate speech often feel it should be regulated, or prohibited altogether. Yet such speech inevitably conveys some sort of idea about a group. It may be a valueless idea or a detestable idea, but it’s an idea nonetheless. This is why state universities that try to enforce prohibitions on hate speech uniformly fail in the courts.

It’s easy for state universities, as government actors, to identify a “compelling interest” in keeping students safe from harassment based on their identities. At the same time, it is all but impossible to draft a speech regulation that, in serving this interest, does not somehow discourage or punish the expression of ideas — however hateful — along the way. Therefore, no such regulation would qualify as “narrowly tailored.”

All of this reflects the fact that the First Amendment was designed to protect speakers from oppressive government action. From James Madison’s essays in the Federalist Papers to modern-day Supreme Court opinions, freedom of speech and expression has been confirmed as a bedrock principle of democracy. According to Justice Louis Brandeis, the whole point of the American experiment was to “make men free to develop their faculties” while fostering habits of deliberation over arbitrary power. This was possible only if people could speak, write, and engage with others without fear of arrest.

But the very loftiness of this vision might leave us wondering if hate speech really merits the protection it receives under established law, particularly in university settings. College campuses are emphatically where people go to “develop their faculties.” However, insulting people on the basis of their identities plays no proper role in this laudable goal, at least in no way Justice Brandeis would have understood. People diminish and pervert their faculties through this kind of speech; they don’t develop them.

Moreover, hate speech has nothing to do with deliberation, the process of intelligent give-and-take by which we pursue the common good in a functioning democracy. This process requires us to respect others. Hate speech refuses to recognize even the innate human dignity of its targets.

In our present moment, marred as it is by dramatically rising rates of antisemitic incidents on campus, it is natural to wonder if, by protecting hate speech, we are forgetting the First Amendment exists to promote a healthy democratic society, on and off campus.

There are two things to note here. First, the First Amendment does not prevent university officials from enforcing rules reasonably related to protecting students’ safety. No one is entitled to engage in conduct or speech that amounts to a “true threat” against someone else. No one is entitled to vandalize university property. When a university punishes someone who defaces a university sidewalk with swastikas, it is regulating the manner of speech, not its content.

In fact, Title VI of the Civil Rights Act enjoins universities to ensure students are free from harassment based on “race, color, or national origin,” harassment that would prevent them from enjoying equal access to an education’s benefits. And, as the U.S. government affirmed in 2019, failure to protect students from antisemitic harassment on campus is also a violation of Title VI.

Second and more crucially, for the purposes of the constitutional analysis the First Amendment in all its rigor applies only to state universities, as “government actors.” Unconstrained by the First Amendment, a private university like Brandeis can go further toward regulating hate speech.

But how do officials at private universities draft regulations designed to protect students from hate speech that do not have the unintended effect of making other students afraid to speak? Can speech be regulated without jeopardizing academic freedom and the free flow of ideas necessary to the educational process?

It is easy — or at least it should be — to identify a call for genocide as hate speech and to draft language that would clearly subject the speaker to some sort of penalty.

“It’s natural to wonder if, by protecting hate speech, we are forgetting the First Amendment exists to promote a healthy democratic society, on and off campus.”

It is much harder to draft language that would clearly not embrace speech that, while perceived by some as insulting, was sincerely intended as a contribution to robust and provocative debate, and was therefore a legitimate part of the deliberation that was so important to Justice Brandeis.

Without this clarity, too many speakers would err on the side of not speaking at all, for fear of incurring some sort of disciplinary process — a state of affairs no university should want.

Perhaps we ought to frame the challenge facing Brandeis and other private universities by hearkening back to Justice Jackson’s famous quote: How do we defend what is humane and decent, without prescribing what is “orthodox.”

Daniel Breen and Rosalind Kabrhel are associate professors of the practice in legal studies.